Hub & Spoke vs. Point-to-Point Networks in the 787 Dreamliner Production

Flynn Casey

HUB & SPOKE

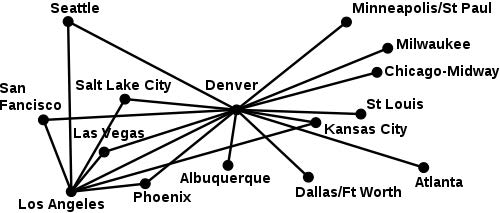

The Spoke-Hub distribution model is a system of connections organized like the spokes and hub of a wheel. In this model, all traffic travels along routes that each connect a node to the larger central distribution center. The model is commonly used in industry (particularly in transport), telecommunications and freight, and in distributed computing, where is it known as a star network. For a hub and spoke network of n nodes, “n – 1” routes are necessary to connect all nodes to each other. In a system with ten destinations, the spoke-hub system requires nine routes to connect all destinations. Often, this means that a hub and spoke system uses transportation resources in the most efficient way. Facilities for complicated operations need only to exist at the hub, rather than at each node, because all routes must pass through the hub before moving to another node. Because of this centralized hub, new nodes can be created easily with only one spoke reaching them. On the other hand, the hub can constitute a bottleneck, where a failure can affect the entire network. Hub-and-spoke is often used as a classification term for a certain style of industrial district that resembles the network. Examples of this include Toyota City, Silicon Valley and Seattle, WA—specifically in the area surrounding the Boeing assembly plant in Everett. Here, the central hub is a large manufacturing corporation such as Toyota or Boeing, while smaller businesses and suppliers that benefit economically from their presence are located in close proximity.

POINT TO POINT

Point-to-point transit refers to a transportation system in which a vehicle travels directly from one node to the other, without passing through a central hub along the way. The main advantage of a point-to-point transportation system is that it allows for greatly reduced travel time as each node is connected to each other directly, although it takes many different routes to do so. In a system with ten destinations, the point-to-point system requires 45 routes to connect all destinations. This type of system considerably reduces the risk of cargo loss—as organization and processing labor is spread between each node—rather than all processing occurring at a central hub. Because of this, a point-to-point network is most beneficial when each node has the facilities necessary to process cargo, albeit on a smaller scale.

In the air-travel industry, most airlines use somewhat of a hybrid system, combining some aspects of hub and spoke and point-to-point networks. These networks have many hubs rather than just one, and offer a selection of direct flights that do not travel through a hub. The point-to-point system is predominantly used by low-cost airlines such as Southwest in the United States, or Ryanair and easyJet in Europe. The system has thus proven beneficial in the air-freight industry, where cargo is often carried in unused baggage space on passenger flights, allowing it to travel quicker and closer to it’s final destination.

787 DREAMLINER

As sales of the Boeing 767 and 747–400 declined in the late 1990’s, the company began developing ideas for new lines of aircraft that could replace these existing planes as a new industry standard. The two major aircraft concepts that began moving towards development were the 747X, a longer, more efficient version of the 747–400, and the Sonic Cruiser, an aircraft that would achieve 15 percent higher speeds while using the same amount of fuel as the existing 767. Out of the two, the Sonic Cruiser received the most market interest, perhaps because Airbus already controlled the market for planes with high passenger capacity. For many aviation enthusiasts, the Airbus A380 and the proposed Boeing 747X represented a move toward a more defined hub-and-spoke system, while smaller, more fuel efficient planes such as the proposed Sonic Cruiser suggested a continuation of the move towards a point-to-point system. The disruption of the global airline market in the wake of the September 11th attacks, coupled with a large rise in oil prices caused many potential customers (airlines in the United States) to back away, and the development of the Sonic Cruiser was eventually cancelled.

Soon after, Boeing announced the development of a plane that would use the technology of the Sonic Cruiser in a more traditional configuration. This was originally called the 7E7, and eventually was renamed to the 787 Dreamliner. The Dreamliner featured many design innovations that aimed to reduce fuel consumption, allowing airlines to offer longer direct flights, as the plane would not need to stop to refuel. The fuselage of the Dreamliner is constructed of single-piece barrel sections made with carbon fiber-reinforced plastic, while portions of the wings incorporate titanium-graphite composites. These materials vastly reduce the weight of the plane, allowing some models to travel over a range of nearly 16,000 kilometers. Boeing marketed this innovation as a benefit to immediate customers (airlines) as well as end customers (airline passengers). For airlines, the benefit is efficiency. The composite components of the plane increase fuel efficiency, reduce the cost of manufacturing, and are more resistant to corrosion. For passengers, the composite portions of the fuselage allow for higher humidity in the cabin, making it more comfortable for passengers. This construction also allows for faster cruising speeds, which, combined with the efficient use of fuel, makes possible more point-to-point direct flights over long distances.

Other innovations that the Dreamliner features are modular engine mounts on the wings, allowing airlines to switch between two types of engines manufactured for the plane, the General Electric GEnx (more fuel efficient over long distances), and the Rolls-Royce Trent 1000 (better initial fuel efficiency). The nozzles of each of these engines are designed with a serrated edge to reduce noise. Additionally, the aircraft features large, light-sensitive windows that work similarly to transition lenses, controlling the amount of light automatically. These features, along with the benefits of the composite sections of the plane, cater predominantly to airlines offering direct international business flights and the passengers who fly long distances often.

SUPPLY CHAIN

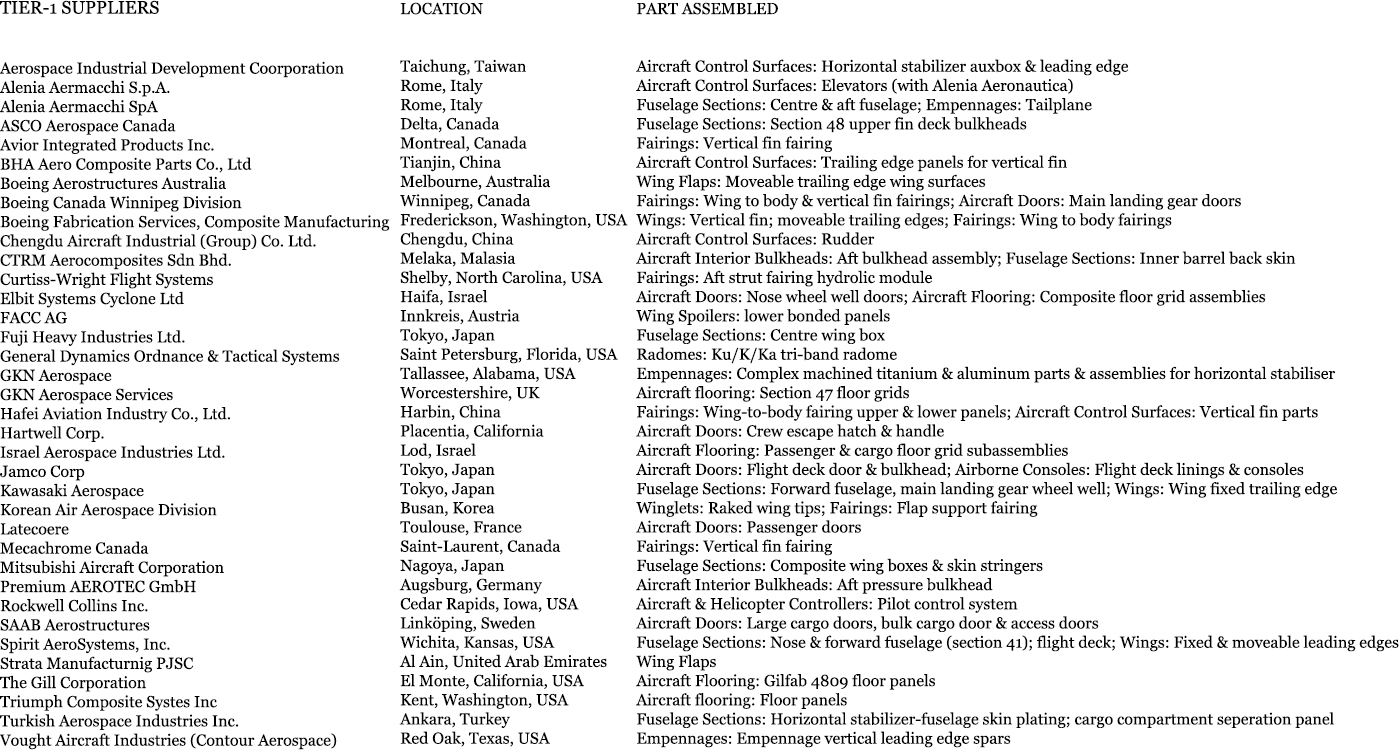

In a traditional supply chain for aircraft production, Boeing works with thousands of manufacturers to produce the individual parts of the plane, which are then assembled in about 30 days at the Boeing facility in Everett, Washington. In response to overwhelming market interest for the new 787 Dreamliner, Boeing had to develop a new model of supply chain in order to produce aircraft more quickly and keep up with demand. For the production of the Dreamliner, Boeing uses a supply chain based on a tiered assembly structure that allows entire portions of the plane to be assembled away from the Boeing facility to then be transported to Everett for the aircraft’s final assembly. With these sections of the plane being assembled off-site, Boeing would be able to complete final assembly of each Dreamliner in three days at the Everett facility. This model of supply chain is new to the aircraft production industry, but has been used by automotive manufacturers (such as Toyota) to develop new cars with quicker development cycles and lower production costs. In many ways the traditional model of an aircraft production supply chain resembles a hub and spoke network, with the central assembly facility acting as the hub and the smaller supplier companies acting as nodes strategically positioned in relation to it. In this case, nodes are positioned according to economic convenience rather than geographic. In comparison, the newer supply chain model used for the Dreamliner production suggests a move towards a point-to-point system. Here, supplier companies are still positioned according to economic and communicative convenience, although the complicated processing (in this case the assembly of the aircraft) is spread between many locations rather than just one. Although Boeing remains the central assembly hub, the nearly 50 tier–1 suppliers (the companies assembling sections of the aircraft) act as many smaller hubs in relation to the tier–2 suppliers (manufacturers of individual parts). In order to transport assembled sections of the aircraft, Boeing developed the 747 DreamLifter, a wide-body cargo plane that would make trips from Boeing’s tier–1 suppliers back to it’s main assembly plants.

787 FUSELAGE TIER-1 SUPPLIERS

LABOR DISPUTE

In Fall of 2008, around 27,000 Boeing machinists went on strike for eight weeks in protest of Boeing’s decisions to outsource much of the production of the 787 Dreamliner, and to hire more contract workers at the Everett facility rather than full-time employees, leaving their machinists with little job security. In response to this strike, Boeing threatened to open a new production facility or move the facility entirely to an anti-union state. While the Boeing production plant in Everett, WA employs tens of thousands of people and its loss would have had an enormous effect on the economy of the area, it was receiving many offers for tax breaks from other states in an effort to bring the company there. Eventually, in 2011, Boeing opened a new assembly plant in Charleston, SC that would share the job of assembling 787 Dreamliners with the Everett plant. The company received large tax benefits from both states. The same year, the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) charged Boeing with a violation of federal labor law by opening a new plant in an anti-union state as punishment towards consistent employee strikes at the Everett assembly plant.

LOCATION

At its core the Dreamliner is an aircraft designed for global business travel. Its innovations cater to airlines seeking to offer non-stop international flights, and its features are most attractive to passengers looking for comfortable long-distance flights. In Boeing’s marketing statement for the plane on their website, they state “[The Dreamliner] reinvents fleet plans and transforms business plans.” In many ways it collapses geographic distance, and moves air travel further towards a point-to-point system and away from a hub-and-spoke system. While globalization is nothing new to the 21st century, products such as the Dreamliner and companies such as Boeing work to increase the speed and scale of global business and economics. In addition, the continuous production of the Dreamliner is entirely reliant on existing global communication and trade partnerships. Accordingly, Boeing has publicly endorsed the Trans-Pacific Partnership agreement—a plan that would accelerate trade between the dozen countries involved, many of which are home to suppliers for Boeing’s airplanes. The trade agreement is equally important for Boeing exports, as the company predicts that airlines in Asia will make up the largest percentage of its customers over the next two decades. Through the course of events that took place around the Boeing labor disputes over the last several years, the physical location of the final assembly of Boeing 787 Dreamliners became very important to the company and it’s employees. As the largest exporter in the United States, Boeing has a huge economic effect on the states it’s assembly plants are located in, even though this geographic location has little to do with the production of the plane itself. Through the company’s refusal to grant its employees the conditions they demand, and through it’s tax negotiations with potential assembly plant locations, Boeing has created a duality in which they are dependent on regulations imposed by individual states as well as trade regulations on a much larger scale, while ultimately developing products that collapse geographic distance.

The Boeing assembly plant in Everett, Washington began operation in 1967, although the company had existed in and around Seattle since 1910. The decision to build the Everett plant was largely due to a lack of space in the older Seattle plant, as the company was beginning production of the wide-body 747. Prior to the labor disputes that began in 2008, the locations of Boeing’s plants had more to do with available space than geographic identity. As the suppliers for Boeing’s parts have become increasingly global, the location of their assembly has had less to do with optimizing production. Although the industrial district where the original plant exists is arranged in a physical hub-and-spoke network, Boeing is now concerned with the arrangement of communication routes–the Trans-Pacific Partnership, for example–rather than transport routes. The products they develop increase the speed and scale of these communication networks, while being entirely dependent on the same networks for production.

In an effort to optimize the production of the 787 Dreamliner, Boeing has created a scenario in which the product relies on the same circumstances it creates. In this scenario, the collective power of subjective laborers has made the company confront the issues of geographic location identity it hopes to circumvent.

- Gunter, Lori. “Boeing Frontiers Online.” Boeing Frontiers Online. July 1, 2002. Accessed October 12, 2015.

- ”Puget Sound Employee Wins ‘Name Your Plane’ Sweepstakes.” Boeing Frontiers Online. July 1, 2003. Accessed October 27, 2015.

- ”787 Propulsion System.” 787 Propulsion System. Accessed October 14, 2015.

- Sodhi, Manmohan S., and Christopher S. Tang. “Application: Mitigating New Product Development Risks—The Case of the Boeing 787 Dreamliner.” Managing Supply Chain Risk International Series in Operations Research & Management Science: 161–79. Accessed October 13, 2015.

- “Boeing 787 Dreamliner - Program Supplier Guide.” Boeing 787 Dreamliner - Program Supplier Guide. Accessed October 14, 2015—http://www.airframer.com/aircraft_detail.html?model=B787.

- ”Simmering Boeing Strike Scorching Both Sides.” The Seattle Times. September 29, 2008. Accessed October 16, 2015.

- ”NLRB.gov.” Boeing Complaint Fact Sheet. Accessed October 16, 2015—https://www.nlrb.gov/news-outreach/fact-sheets/factsheet-archives/boeing-complaint-fact-sheet.

- Jansen, Bart. “Boeing CEO Endorses Progress on Trans-Pacific Partnership.” USA Today. October 5, 2015. Accessed October 20, 2015.