The Reeducation of an English Major: STEM in Silicon Valley

Amelia Furlong

The student is looking at me with an expression akin to glowering. It is nine o’clock on a Friday night, and I know she would rather be anywhere but here, writing college admissions supplements in a starkly white classroom with unidentifiable stains on the walls.

"Well what do you like about engineering?" I ask her. We are working on a ’why major’ essay for Purdue University and she is being intractable.

"I don’t know what I like about engineering," she says, and then smiles self-consciously. She knows how childish she sounds.

She’s a smart kid, but she’s had a rough time of it recently. She has lately acquired a boyfriend—another student of mine, and a paragon of the awkwardly sweet teenage boy falling in love for the first time—after which her mother has proceeded to ground her, take her phone, forbid her to see said boyfriend, and relocate her to a branch of the college counseling company where I work that he does not frequent. I’m not entirely sure what the mother’s objection to the boyfriend might be—perhaps she is just like mine, and the idea of her teenage daughter dating anyone horrifies her—but I suspect it has something to do with the fear that a boyfriend will distract her daughter from the carefully drawn path that has been set for her; a path that includes straight A’s, a full ride to Stanford, a career as a successful engineer, and then, presumably, death. It is not unprecedented: I see this fear in all my students’ parents.

This student, along with the five others that are watching this exchange, is a second-generation immigrant. Her parents came from China and settled in the Silicon Valley, hoping to give her a better life. The pressure on her and her peers is enormous. At least, that is what I have gleaned from the numerous Common Application essays about being the children of immigrants that I have read and then vetoed because they were ’cliché.’ But as much as this might be policy of my company, I enjoy reading these essays. In them, my students confess to the anxieties and insecurities that crowd up against their lusty, joyful, carefree thoughts. They write of their parents’ pasts, usually shrouded in poverty, and of their fears that they won’t be the perfect, successful children they are expected to be. It is not so much that my students’ parents are trying to guilt their children into success, so much as they only really have one way of defining success. Okay, maybe three: a career in engineering, computer science, or medicine.

So I try to ask her gently.

"Is there a particular engineering experience you’ve had that stands out to you?"

"...not really."

"Are your parents engineers?"

"Yeah. But that’s not why I want to be one."

"Then why do you?"

She pauses, staring at her laptop, before looking up at me again. The smile is back.

"Can I write about a time at the engineering summer program I did when a bunch of guys were really controlling and wouldn’t listen to any of our ideas?"

"Maybe. What happened?"

"There were seven of them and two of us—girls—and they didn’t think anything we said was worthy of consideration. They would just roll their eyes even though of course our ideas were better."

"How did this make you feel?" Often, these workshops feel like therapy sessions.

"I was annoyed, but it didn’t make me want to give up. It made me want to be better than them. If you want to be a good engineer, you have to crush them."

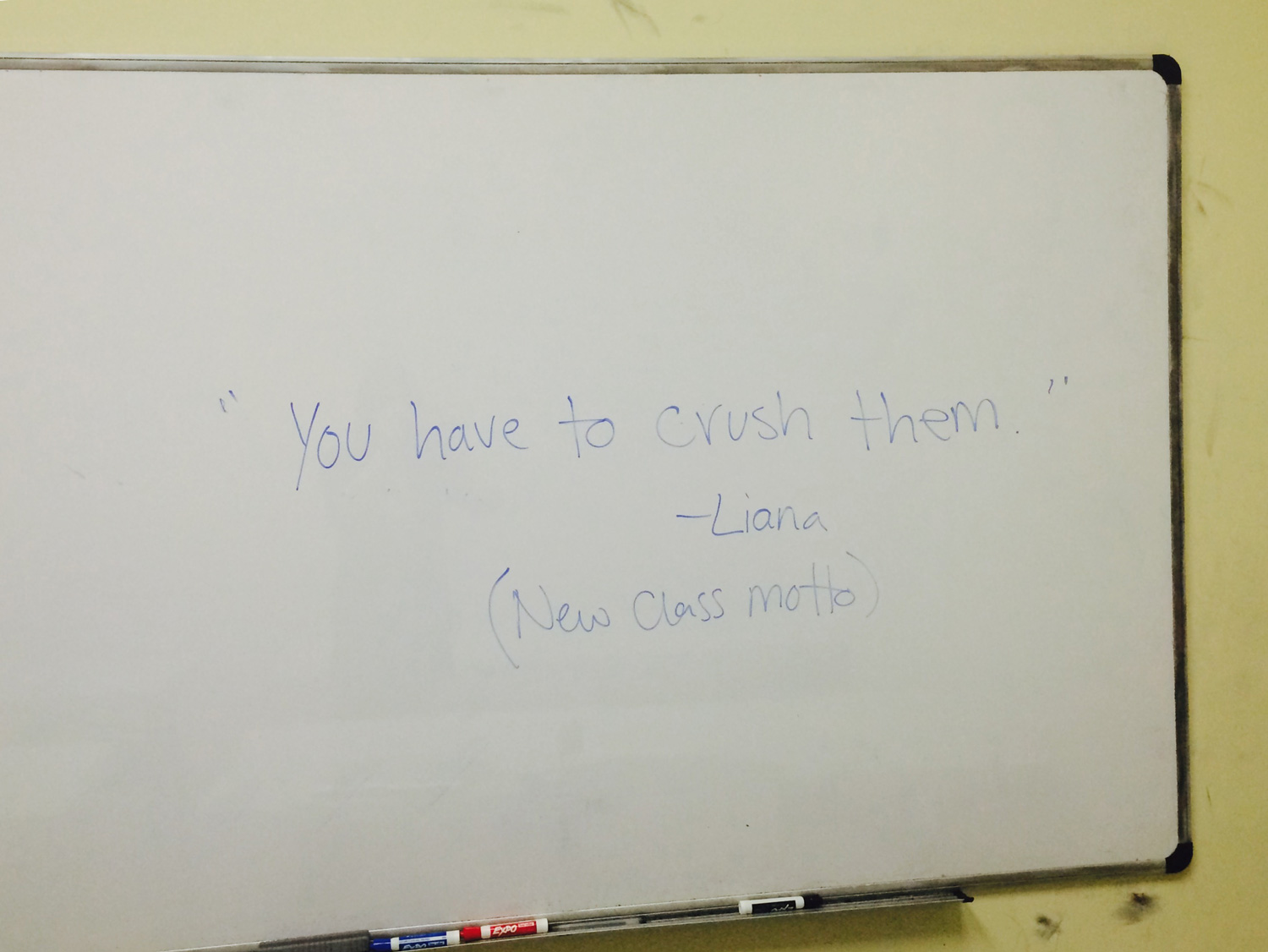

At this, the other female students begin to laugh; she smiles in acknowledgment, while the lone male in the room announces his intimidation and fear of her, although I suspect he actually thinks she’s cool. I end up writing the phrase on the whiteboard, our new class motto: "You have to crush them."

I like this about my students, especially the female ones. Even though they are being raised in such a manner that an A- warrants disapproval, and a boyfriend is less an important learning experience than an interference from studying, they are being taught that womanhood means crushing boys in their Cal Poly engineering programs, or winning robotics competitions, or programming video games. This mindset is ubiquitous. Not a single one of my female students, all except two of whom are Chinese- or Taiwanese-American, has expressed any fear at the prospect of entering a traditionally male-dominated profession; and all of them, except two, are planning on pursuing engineering, business, or medicine. Another student articulated this to me recently. A top student, and a brilliant musician and painter, she plans to major in computer science in college.

"Our society has made girls believe that they are more fit for the humanities then STEM," she told me. She knew that she could study art or music—or literature—but pursuing STEM was as much about following her passion as it was about proving to the world that she could.

Of course, it is probably also about making money.

I knew my student wasn’t considering how her pronouncement would sit with her audience when she said it, but I was still taken aback by her words. She was speaking to a female liberal arts graduate, after all, whose background is steeped in all corners of the humanities. I studied English Literature at a small liberal arts college in the Northeast, and I never considered that this made me less of a strong woman. Indeed, the more entrenched in collegiate literature I became, the more I felt I was being exposed to progressive, queer thought that was challenging my notions of gender uniformity and rigidity. I learned how to talk about race, and privilege, and when to shut up and listen to others talk about race and privilege. I learned about abuse, and violence, and their omnipresence. I learned how to express the things that had happened to me, and how to be an ally when those things happened to others. The further I chased after my intellectual goals, the more I felt that the choice to study literature was less about being ’bad at math’ and more about being "good at being human."

And anyway the irony is clear: what my students consider a "woman’s" discipline, has, in the long tradition of liberal education, been reserved for men until very recently. Women’s entrance into the humanities has been hard-won. It is a field that is the providence of male writers; even today, very little of the fiction that we read in high school and college curricula are by female writers. Even fewer philosophy books. And yet, I knew what my student meant: the humanities, in their essence, are about interrogating and investigating ideas of truth; the realm of cold, hard logic is sidelined by the more emotionally-driven, probing search for "the meaning of life." Not to say that logic is missing from the humanities, rather it’s that one logical system replaces another. Scientific logic is replaced by contingency, and interpretation, formulas by context-based approaches. Still, speculation somehow has been associated with inconsistency, and inconsistency with an emotional rather than a strategic approach to meaning. While the humanities might seem masculine to the ancients, as well as the university student of the nineteenth century, to a high schooler who has been raised with the belief that women cry over their feelings while men shoot things, it is more likely to be associated with femininity. Such a problematic characterization demeans the nobility of the discipline for both men and women.

I think if I explained this to my student, she would agree. But her comment was more insidious than she intended it to be. I want my students to pursue the dreams that they have envisioned for themselves, and if my job has taught me anything, it is that techies are not all sellouts, no matter what all the San Francisco artists being forced out of their homes might tell you: some techies really, really love coding. But it shouldn’t follow that because the tech field can be fun and liberating for women, that the humanities are not. So if STEM empowers girls to reject the sexist restrictions that have been imposed upon them, then how do we get the humanities to empower them as well?

In his inaugural address to the University of St. Andrew’s in 1867, John Stuart Mill made the case for a liberal education that leaves room for—encourages, even—the study of science and literature in tandem. This will create, he argues, the best, most humane, and most articulate students of humanity. "[To] This question," he tells us, "whether we should be taught the classics or the sciences... I can only reply by the question, why not both? Can anything deserve the name of a good education which does not include literature and science too? If there were no more to be said than that scientific education teaches us to think, and literary education to express our thoughts, do we not require both?" And, he finishes, in prose so colorful I am left in no doubt that he has more flourishes up his sleeves than the ancients did: “"short as life is... we are not so badly off that our scholars need be ignorant of the laws and properties of the world they live in, or our scientific men destitute of poetic feeling and artistic cultivation."

It is one of the best defenses of the classical and scientific educations that I have ever heard, and one that makes me pause and reconsider the relevance of my students’ majors. However, Mill could not have predicted the advent of the Internet, which brought with it the need for programming, and with that the potential to make obscene amounts of money at a very young age by sitting in front of a computer screen. What Mill thinks of as scientific education, in which one is taught how to think critically through hypothesis and analysis and to understand fundamental natural laws, is hardly the vocation of computer science. I have heard the study of programming compared to the study of a language, and this comparison seems apt. But so far I have yet to see how programming pushes the programmer to grasp the "processes by which truth is attained" through careful reasoning and observation. If there is one thing that I fear about computer science, it is that it is a succubus that has ownership over the souls of my students, who should be looking for the profound realization of truth, rather than turning their educations into a utility.

This is not to say that all my students will be partaking in soul-sucking rituals the moment they reach undergraduate. One student wants to use her computer science degree to make applications that integrate technology and music, so that music composition and appreciation will be accessible to more people. Another student wants to design video games, and I know that she will go on to great success engineering games that do not feature the torture and mutilation of women or encourage the proliferation of gun violence.

If there is one reason why the dawn of women engineers and computer scientists excites me, it is this. We need these kinds of thinkers, designers, artists, and, yes, programmers. However, what strikes me about both of these students is that they are readers; they engage with the humanities; they look at great art. Part of me wonders if they would be artists, or writers, under different circumstances. But they were raised with technology. Whereas I was raised without television and in a house sagging with books, my students were raised playing with videogames and other electronic toys. They see lines of code and complex machines as vehicles for creativity, just as I once saw my dress-up clothes and quills and ink as means of artistic expression. To call one superior over the other would age me, make me irrelevant, and put me in the ranks of curmudgeons like Jonathan Franzen. There is something lush and romantic about my childhood, and sometimes I catch myself wishing it upon my students, but I have to check myself when such thoughts occur. There is nothing harmful in how my tech-savvy students see the world, or in how they want to express themselves in it. After all, when they are reading as often as they are designing apps, are not they embodying John Stuart Mill’s pedagogy—embodying it much better than myself, even? Where is my investigation into science? I am forced to wonder every time I ask a student to explain to me what she means by “RPGs” and “cloud computing.” Am I wasting the brief amount of time I have on this earth by remaining ignorant of the laws and properties of the technological world?

I might ask my students to teach me JAVA, just in case.

My female students are going to become powerful women. They are going to run tech companies, found startups, and fund global initiatives in support of women’s rights. Many of them will take the time to read about gender and violence, race and exclusion, but others won’t. That’s why I’m teaching them, I suppose. That’s why I send them links to John Stuart Mill inaugural speeches and Ta-Nehisi Coates articles. Because while they may be strong, liberated women, I want to make sure they are also strong, liberated humans.

Humans who can crush them all.

back to the top ⤴︎