Low Profile: Privacy on social media

Buffy Cain

A few years ago, Facebook outed me to my father after I joined a closed LGBT Facebook group. This action was posted as content on the public timeline via the so called “frictionless sharing” feature, which posts user activity automatically and without notification. Thankfully, my dad was cool about it, and immediately hit ’like’. While I was lucky in that this particular experience didn’t involve homophobic backlash, I nonetheless would have strongly preferred to have control over when and how this sensitive information was revealed. Today, I’m aware that in addition to being subject to forced social sharing on Facebook, the company also sells my information to advertising firms, and shares it with the NSA. The choice seems to be between complete refusal and submission to surveillance and forced oversharing. Despite the risks, I’m not only still on Facebook, but I’ve also set up accounts since my outing: on Twitter, Instagram, Skype, Google+, and Tumblr, as well as a suite of apps that track my moods, exercise habits, hormonal cycles, sleeping patterns, and budget. Yet, I still maintain that I am a reserved and private person, partially because I don’t feel exposed when I’m logged-in; I feel submerged, shielded.

The knowledge that I am not alone in this contradictory constellation of preference, action, and experience is at once a consolation and a torment. I’d like to examine the conditions under which people sacrifice privacy, and the possibility that the decision to do so reveals a preference for publicity over privacy. I will also consider a narrowed definition of privacy in order to resolve discord between the experience of being online and the reality of surveillance.

In order to talk about why people are willing to give up privacy, we first have to define ‘private’ and ‘privacy’. I’d like to suggest that privacy is a type of control exercised by concealing specific information in order to manage a social situation, and that this control is achieved through a variety of social practices configured by structural conditions. Context determines which information is private, and as circumstances change so to does the privacy status of a given information item. My youthful misadventures, gender identity, sexual orientation, and ideological attitudes are all potentially private, as this information could be used against me. An illustrative case: information gleaned from social media profiles can form the basis for legal decisions. If social media accounts were subject to scrutiny by a court in order to justify a claim of emotional damages, then it would be in the interest of the user to protect the privacy of any information which might frame them as law-abiding. In this context, protecting privacy means exercising agency and precise control in limiting and directing flows of information from social media accounts.

Under what conditions are do we give up privacy? Our ability to act in our own best interests is constrained by the availability of information, our own cognitive capacity, and the complexity of the decision problem. Perhaps the conditions under which the decision to sacrifice privacy occurs fully explains the irrational behavior I’ve noted.

Participants in digital culture (let’s call us netizens) operate under the condition of low information availability as a result of government and corporate opacity. It is in the interest of the powerful to remain occluded while requiring followers/users/citizens to remain exposed, thereby arranging information asymmetries in order to further enable the extraction of surplus value. As users become aware of the extent to which social media services coerce users into publicizing their activity and the extent of corporate and government surveillance of user activity, they may opt for refusal. And in fact, higher information availability following the release of the Snowden documents detailing government surveillance practices precipitated a user exodus that had real impact on the bottom line of the major tech companies.

Netizens also occupy an environment in which an ideological argument for transparency and publicity is advanced in bad faith. We’re not always capable of detecting when we are being manipulated into pursuing an ill-advised course of action. Perhaps to some extent or in some cases, individuals’ continued participation in digital realms where they are subject to surveillance hinges on their acceptance of surveillance as a societal good. Facebook has adopted a hypocritical, moralizing tone when discussing the public’s privacy concerns. Mark Zuckerberg has said that Facebook’s real name policy--which unfairly harmed LGBT individuals, indigenous individuals, artists, and performers--is justified on the basis that “having two identities for yourself is an example of a lack of integrity”. If the companies advancing radical transparency believed their own line, they’d design transparent systems with, for instance, opt-in instead of opt-out feature updates, notifications for users when their data is given to marketers/the NSA, or notifications for users when their content is accessed by a partner. These policies are not in place because radical transparency is an effective corrective against societal ills, but because user transparency coupled with platform opacity generates profit.

However, Edward Snowden’s use of Twitter demonstrates the possibility of continued engagement with social media despite fundamental ideological disagreement with the practice of surveillance and awareness that the social media activity undertaken is subject to surveillance and commodification. What does Snowden and what do we feel that we stand to gain in sacrificing privacy? Privacy exists in tension with publicity. That is, as publicity increases privacy tends to decrease, following from their function. Privacy reduces information outflows such that the information we convey remains local and high-context, while publicity serves to amplify outflows, though often in heavily decontextualized or decrepit form. Many people willingly sacrifice their privacy precisely in order to gain access to a public audience. This is apparent in the extreme example of the reality TV personalities who grant near-total access, but operates on smaller scales as well (e.g. to present an opinion at a coffee shop discussion group, one must present oneself at the shop in full view of the shop’s employees and one’s fellow customers). Strikingly, the structural conditions that configure publicity, configure privacy in its negative image.

The public sphere is the site of this configuration of publicity and privacy. Jurgen Habermas characterizes the public sphere, which he situates historically in Enlightenment Europe, as an inclusive space existing outside state and church authority where individuals gather and participate in discussions of common concern without regard for social status. According to Gardinar, Habermasian subjectivity is marked by “an interchangeable, ‘minimalist’ body’... subtended by a rational mind that engages in purposive dialogue and moral reflection. Such a Habermasian body does not seem to be marked by difference, of a gendered nature or otherwise.” Discussions of the public sphere spurred the establishment of publishing enterprises, and gradually, state authority, which previously had just been represented before the people, was publicly monitored and critiqued in the press by the bourgeoisie. Men of means and letters thereby destabilized the authority of the monarchy, and fostered the development of a new sort of influence, that of media power. Habermas’ characterization of the public sphere and his historical examples exist in stark contrast to each other. The public sphere aspired to the ideals he notes, but instead served social domination in the guise of deliberation, advanced a problematic definition of the common good, and excluded individuals based on class, race, and gender.

Social media can be described as a kind of public sphere, perhaps unsurprisingly, given the tendency of the digital to extend pre-existing interests, concepts, and institutions. Consider Twitter, a maximally inclusive, deliberative platform for discourse in which no agent (the prevalence of Twitter bots is maybe the revenge of Habermasian subjectivity) is prevented from commentary on the basis of their status. For the first time, many of us have an opportunity to be involved in a public sphere. Some might find that they are willing to submit to surveillance and sacrifice privacy, if platforms also act as sites for discussion, organizing, and activism.

Social equality discussions have thrived online, often to the extent that their concerns have erupted into real life demonstration, direct action, and legal advocacy work. Black Lives Matter, a movement organized around the issues of police brutality towards and mass incarceration of black Americans, began as a twitter hashtag, built power through protest, and now helps to direct the discourse surrounding race in America. The internet arms the activist with a set of tools and abilities that are well suited to organizing. The higher degree of inclusivity and connectivity on the internet has made it easier for individuals to raise awareness of a cause. Organizers can send notifications and updates cheaply and quickly via mass email and listservs, an ability which is especially important in areas where atrocities or critical needs would go otherwise unreported, and fundraising, particularly from small donors, has become easier and quicker due to sites that allow online money transfers. Clearly there is much to gain in using the tools of social media, especially for individuals who would otherwise have limited access to a public platform. The choice to submit to corporate and government surveillance is not irrational, but comprised.

One final wrinkle: I don’t often feel like I’m horribly exposed by our existence in digital spaces that are under surveillance. If anything I feel enveloped and safe. In my view, this is because we relate to privacy not in the abstract but vis-a-vis specific situations, specific audiences, and immediate surroundings. Certain online spaces by virtue of their decontextualized nature allow us to play with notions of identity, commitment and meaning, without risking the consequences that are involved real identities and relationships. We’re safer online, in a sense. Offline, we are unconditionally committed to our identities, and are therefore constantly exposed to social risk. The privacy threat posed by surveillance is both abstract in nature and in effect. Being under surveillance poses no specific risk of social embarrassment.

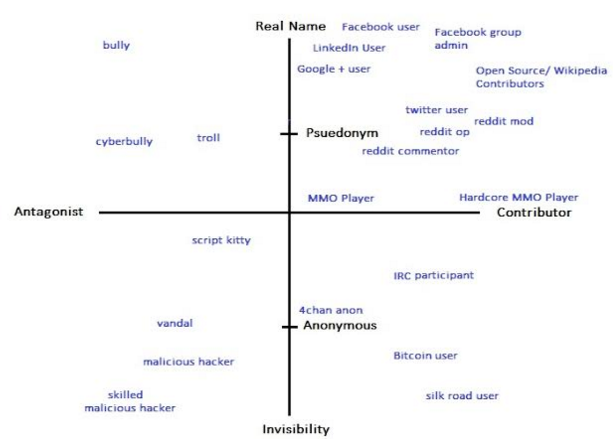

Online, we are active to various degrees (antagonism, lurking, or contribution) and personally invested to various degrees (pseudonymity, anonymity, or invisibility) in overlapping competing public spheres. Some sites are demanding a high and increasing level of personal investment or contribution by consolidating of separate online identities, as when Google started unilaterally associating YouTube accounts with Google+ accounts or when Facebook insisting on real name use and frictionless sharing. Many users felt that their privacy had been violated when comments left in Youtube under the conditions of pseudonymity were associated with their IRL/Facebook/Google+ handle. We feel embarrassed and defensive when bosses, family members, or friends recognize content produced under a pseudonym as our own, because we’re suddenly unconditionally committed to this content.

In treating the internet as if it were our therapist, priest, dermatologist, financial planner, shopkeeper, or surrogate grandmother we trade the immediate concrete risks of revealing our health, sin, and wealth to our social peers for abstract risk involved in surveillance. I do not mean to diminish the evil of surveillance, as this feature of disciplinary societies has a chilling effect on life and a punitive effect on individuals.

In closing, I’ll offer some advice: if you’re concerned that the siren song of publicity will tempt you to submit to surveillance, lash yourself to the mast of pseudonymity, anonymous networks, and cryptography.

[A note: the terms public and private also come up in discussion of municipally owned vs privately held property. It might be interesting to note that the spaces Habermas offers as examples of the public sphere—coffee houses and salons—were also privately held, often charged admission, and were engaged in the process of accumulation of information capital. One such coffee house, Lloyd’s (est. 1688), slowly transitioned from coffee house in which insurance matters were occasionally discussed to insurance market. The corporation still exists today, and raked in 2.7 billion pounds in profits last year. The emergence of Habermas’ public sphere coincided with both increasing democratization and increasing privatization.]

back to the top ⤴︎