Accumulation and unraveling of the self

Thea Ballard

“If relation exists as a pathway between entities in a multi-dimensional network wherein those entities themselves are the product of particular sets of relations, then moving across those dimensions and through its infinite relational web will entail an undoing we may not want to experience or acknowledge as such” —Lee Edelman, Sex, or the Unbearable

I’ve spent several chunks of time, beginning in my late teens, working with (older, female) mental health professionals to produce narratives that might allow me to understand, and perhaps alleviate, a sometimes-debilitating generalized anxiety that often manifests in the form of dissociation—slipping back from the world, a film of elsewhere separating me from my surroundings, my body, my voice. When it’s been at its worst and most durational, compulsively vocalizing these sensations to others has been the only way to feel moored, real. In therapy, I offer an untidy collection of experience, sourced from memories, present desires, banal day-to-day occurrences, fragments of dreams, what have you; in a room whose static spatial attributes themselves offer a framing infrastructure, she gently plies this into something that possesses enough order that we can return to and build upon it. At 17, I read Joan Didion and, aglow as diary-keeping small-town 17-year-old girls reading Didion for the first time tend to be, consumed her line from The White Album with no needed context: “We tell ourselves stories in order to live.”

When it’s tended to correctly, narrative operates as a therapeutic technology—one that works in part by bringing the narrator closer to herself. It can, of course, be accessed outside of a traditional psychotherapeutic relationship through an array of media; my psychotherapeutic journey could arguably be expanded to include my own proclivity for various forms of diary-keeping, many of which are public and aestheticized in some way: songwriting, Livejournaling, first-person essay writing. With particular attention to the ways we learn to speak about and see ourselves—produce self-narratives, that is—via social media, here I consider art practices that make use of narrative accumulation and self-documentation, diaries and work that mimics their form.

In a 2013 paper, Rob Horning describes his notion of of a “postauthentic data self,” considering how, under networked capitalism, “authenticity as fidelity to an autonomous, unified a priori self becomes untenable.” This data self is produced through essentially obligatory participation in social media, and is rendered rational through templates and algorithms, rather than learning to express a pre-existing, pre-linguistic coherence; “the self’s basis of reality shifts from the past to the future,” Horning writes, “where the templates of social media hold the self in place and reveal it as it emerges.” This has narrative implications, unsettling, maybe, the sense of futurity—of the possibility of emerging from a muddled, yearning present into a coherent tomorrow—embedded in projects of becoming. And if there’s no essential self waiting to be uncovered within all this language, what does the therapeutic self-narrative bring one closer to?

Still from Moyra Davey's 50 Minutes, 2006.

Still from Moyra Davey's 50 Minutes, 2006.

Moyra Davey’s 2006 film 50 Minutes recounts the artist’s time spent in psychoanalysis, one example of the genre of artworks that evoke the therapeutic environment. The length of a therapy session, the work is shot in Davey’s signature self-portrait style; the artist films herself primarily in her apartment, narrating as the camera zeroes in on the minutiae of her domestic life. Some kind of autobiographical storytelling is ostensibly occurring, but it loops around and stretches across images that, however intimate-looking, tell us less than we’d expect them to. Her voiceover monologue is cast as a performance from the video’s start, where she starts and stops in response to direction on her delivery from someone offscreen. Throughout, as her voice generates the video’s rhythm, Davey’s body passes in and out of her tableaus. Recounting the nature of her uptown sessions with a psychoanalyst-in-training, she says, “It was all very ritualistic and formal.” This session, however, is not.

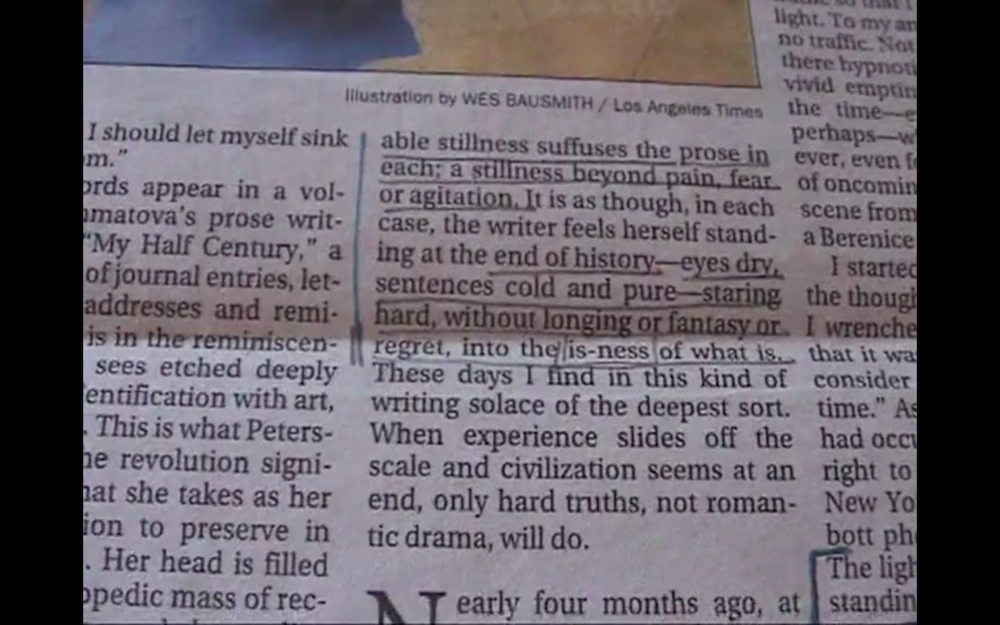

She talks a lot, also, about books, disassembling what might otherwise be a linear account of the experiential architecture of her analysis by splicing in vignettes drawn from the likes of Vivian Gornick and Svetlana Boym. We read with Davey, her camera zooming in on the annotated newspapers and paperbacks—accessing a kind of interiority as she projects outside herself into others’ narratives, fictional or otherwise. While Davey’s visual and cultural language doesn’t seem to have much intentional overlap with that of the Internet and its attendant subcultures, the piece is nonetheless weirdly reminiscent of how users self-narrativize on social media, particularly in this fragmentary digestion of texts.

Maggie Lee’s 2014 film Mommy is also a collage, albeit with an aesthetic far more indebted to internet culture than Davey’s 50 Minutes. Lee uses autobiographical storytelling to specifically cathartic ends; the film is a tribute to her late mother, whose New Jersey home Lee was sorting through and cleaning up as she made it. She emerges in the piece (which, borrowing heavily from her own diaries, is as much her coming-of-age as it is her mother’s story) through the constant interjection of cultural fragments: She is constituted through the songs, magazines, and parties that have been important to her; through the fashion trends she’s loved over time; through Facebook photos and blog posts. An erratic narrator, the timbre of her voices changes in goofy, sometimes gently self-mocking ways as she gives voiceover to images of her as a child, or her as a Brooklyn club kid, and applying meme-like text to old home videos and photographs, she digests artifacts from over two decades into a single present moment. In a manner similar to 50 Minutes, the process of collaging provides the film’s gravitational center. What’s therapeutic here is not so much how Lee’s mother, or Lee herself, emerges out of these combinations, but the joyous habit of layering images and memories. “’Becoming oneself’ has turned into a crappy job—a compulsory low-paying, low-skill job,” Horning writes, but the affect of Mommy (as marked as it is by the consumer labor that goes into coming of age on social media)—the ecstatic, celebratory approach Lee takes to collage—would suggest otherwise.

Even in the middle of various forms of becoming, Lee and Davey are both prone to looking back. Davey seems self-conscious of her affinity for nostalgia, which, she’s heard, “is the intellectual’s guilty pleasure.” But in 50 Minutes she works to better locate this affect: “In critical circles nostalgia has a negative, even decadent connotation. but the etymology of the word uncovers other meanings,” she says. “It comes from the greek nostos, a return home, and algos, meaning pain. After homesickness and melancholy, regret in the dictionary, there is a third definition of nostalgia, which is unsatisfied desire, and that is what the word has always implied to me: unconsummated desire kept alive by private forays into the cultural spaces of memory.” This definition of nostalgia leaves room for memory and future-facing desire to collapse into one another, a collision that produces Lee’s ecstatics and Davey’s more angular moments of longing—the microerotics that lodge these projects in the viewer’s subconscious.

In the first chapter of Sex or the Unbearable, a dialogue between Lee Edelman and Lauren Berlant, Edelman uses the futurity inherent in storytelling to outline the optimism he and Berlant wish to pull apart from their discussion of sex. He writes,One way to tell our story is by starting with the problem of story as such and considering how telling it is that we tell our stories here so differently. However attenuated, qualified, ironized, interrupted, or deconstructed it may be, a story implies a direction; it signals, as story, a movement that leads toward some payoff or profit, some comprehension or closure, however open-ended… Even in those moments when we imagine ourselves immersed in its permanent middle, the story, so conceived at least, moves through time toward its putative end, where it seems to define the field within which it produces its sense of sense. Absent that framework of expectation, it isn’t a story at all, just metonymic associations attached to a given nucleus.

It’s compelling, in the cases of Lee and Davey, to think of “becoming” as an action that can occur without an ultimate narrative arrival: as a state with no endpoint, no horizon, one that’s as much about feeling extremely distant from oneself (or the possibility of a self) as it about moments of feeling whole. Virocrypsis, a 2015 video work by Andrea Crespo, articulates a sort of loop of becoming in this vein as well. Not diaristic in a conventional sense, the work articulates sensations of living in multiplicity, exploring teratological subjectivity through a dialogue (in text, never in voiceover, grounding the piece in the discursive social space of the internet) between the illustrated avatars Cynthia and Celinde, who share a body. Cynthia and Celinde exist in the space between, maybe even in spite of, psychiatric diagnoses, “luring, reprogramming since our early years.” “The host slowly begins to realize its interior schizzes and discontinuities, that it is not one,” they say. “That we’ve never been so. It unravels and liquefies.” Embedded in communicating this state of being is a hope, also, that they might “help others affected”—their storytelling cast within a framework that’s healing, in the sense that they see a therapeutic potential in this unraveling.

Along with illustrations of Cynthia and Celinde, the visuals that accompany this dialogue are those of a sustaining machine. There are whirring motors, data scanners, screens. Recurring is an image of splintered glass (dusty and speckled not unlike another backdrop they use, of what looks like a faraway galaxy in greyscale). Austere and unfinished, this becomes the backdrop for a kind of erotics employed by the multiple narrators; there is “suturing,” “entangling,” “liquefying,” “viscous vibration.” Berlant and Edelman take interest in sex and negativity as an “encounter with what exceeds and undoes the subject’s fantasmatic sovereignty.” The splintered glass in Crespo’s film for me, offering cracks through which to slip, best contains its free-falling, protean erotics; it’s also what bookends the narrative.

Lately I’ve been seeing someone who says she can guess when I slip outside of myself into a dissociative state because she gets dizzy. Knowing that we’ve come ungrounded together doesn’t pull me back into myself, as I’ve wondered if she’s maybe trying to do. But increasingly it feels like a rich point of relation, of being seen, offering some potential that a sensation defined by distance and an utter lack of coherence can also be one of closeness and embodiment. In these moments, the nature of my own narrative compulsions shifts, as does my subject-position as a viewer or listener, making me attentive to my own dizziness in these aestheticized, unconventionally psychotherapeutic moments of relation. Spinning out narrative as a means by which to care for ourselves and others becomes less about tracing a path than creating holes in a web through which we might fall. ~*

Thea Ballard is..