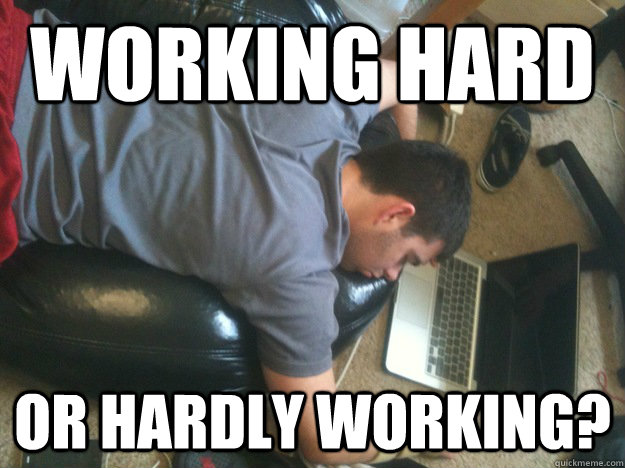

Recline Decline: Working Hard or Hardly Working

Whitney Mallett

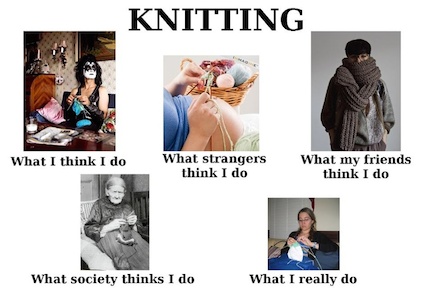

The category of hobby is easiest to pin down when labor and leisure are clearly defined, but in the current Information Age, they aren’t. As digital technologies continue to change the way we work and play, the boundary between them is progressively disintegrating. Full-time jobs are scarce and full-time or part-time, a lot of employees are glued to smartphones, expected to always be on-call. Others are left juggling the erratic schedules of several different gigs, and when they do have a little downtime to unwind, it's often posting content or playing games online. Even offline moments of #metime, going for a run, knitting a scarf, or baking chocolate bacon cupcakes, frequently end up performed for instagram. The hobby landscape looks a little different than it used to.

Like modern dog ownership, hobbies as we know them became popular around the time that the middle class emerged.123 Near the end of the 19th-century, needlework and quilting became mainstream American pastimes at the same moment there was a movement fighting for the eight-hour workday. One of the movement’s slogans neatly divided the day in three: “eight hours for work, eight hours for rest and eight hours for what you will.” As more unions won the eight-hour workday, more people had a spare eight-hours to fill with whatever they wanted to do.

"In Dogs We Trust the Book: A Survey of Modern Day Dog Ownership by Ollie Grove and Will Robson-Scott" Hypebeast. February 24, 2015.

A story about leisure is, of course, a story about work. But hobbies occupy a strange liminal space between the two. They are work we do when we don’t have to be working, work that we take pleasure in. They’re born, in some measure, out of self-alienation, a need to identify as a golfer rather than an office clerk, a knitter rather than a call-center operator. But the activities we choose to fill this void are often extremely labor-intensive. “Perhaps in part, hobbies are a utopia of labor,” author and theorist McKenzie Wark suggests in an email. “It’s how people would work if they had the choice.”

Most people don’t get a choice. Having a vocation rather than a job is typically a privilege of a certain class, and so it’s a middle-class predicament to be looking for fulfillment in work outside the workplace. It might be hard to pin down precisely what is a hobby, but collecting stamps screams hobby more than collecting Basquiats. Hobbies aren’t just “not work”, they are what you do when you are not working, and they aren’t quite the same as pastimes that fill a life of leisure.

But as full-time jobs become scarce and the boundaries between work and play get hazy, what a hobby is seems harder and harder to define. Is playing Candy Crush a hobby? What about needlepoint if you’re then selling your wares on Etsy? “There’s ambiguities about the category,” notes Wark, “When there’s full time, secure work, hobbies are a voluntary past time for most people. On the other hand, when work is less permanent or secure, I think that is when people are more likely to want to make money off of it.”

There are 7.5 million Americans, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, working part-time because they can’t find full-time employment. New tech is partly to blame for the demise of the 40-hour work week in a few different ways:

Real-time data analysis has changed staffing. “Along with virtually every major retail and restaurant chain, Starbucks relies on software that choreographs workers in precise, intricate ballets, using sales patterns and other data to determine which of its 130,000 baristas are needed in its thousands of locations and exactly when,” Jodi Kantor explains in The New York Times. Staffing this way means employees have erratic schedules and fluctuating hours.

Mobile apps and online marketplaces like Uber, Lyft, TaskRabbit, Postmates, Etsy, and AirBnB have normalized piecing together an income. The slick branding of the so-called sharing economy has made piecemeal labor seem innovative rather than precarious. The flip side of the gig economy is Silicon Valley where the IT talent behind these and other start-ups tends to work. In this aggressive corporate culture, 55, 60, even 70-hour work weeks are common. “Working marathon hours is part of Silicon Valley’s DNA,” Joscelin Cooper, a former tech industry professional, noted in Forbes.

For those depending on dwindling hours and piecemeal labor, hobbies can be an extra source of income, and online marketplaces make going pro more accessible. Etsy has 1.4 million registered sellers hocking embroidered dog bandanas, crocheted baby booties, anthropomorphic ceramic planters, personalized pet memorials, Justin-Beiber-is-my-Bae T-shirts, felt cat beds, feather hair extensions, and every other handmade, vintage, or twee thing you wouldn’t want to imagine. According to a 2015 study of 4,000 US Etsy sellers, 70 percent have another occupation and 17 percent have an annual household income below $25,000, which is just around the poverty line for a four-person household. The engine driving this dismal economic reality is the fantasy of making a living doing what you love.

What the people on Etsy love seems to be roughly the same as what 20 and 30-somethings moving causing white infill in urban centers all across the country love: all things handmade, artisanal, and old-timey. Since emerging in Portland and Brooklyn, the dream of the 1890s characterized by straight razors, pickled beets, and crocheted murals has spread to dozens of mid-sized American cities. The resurrection of out-dated modes of production, however, isn’t totally new. Hobbies have always tended toward being old-fashioned and antiquated. In her book Hedozining Technologies: Paths to Pleasure in Hobbies and Leisure, writer and historian Rachel P. Maines, explains that as work became increasingly mechanized, hand methods of production like weaving and carpentry became anachronistic and then hedonized—crafts we chose to do rather than work we had to do. With the artisan revival intersecting head-on with the rise of micro lifestyle branding, the dream of turning crafts into small businesses seems to be more alive than ever.

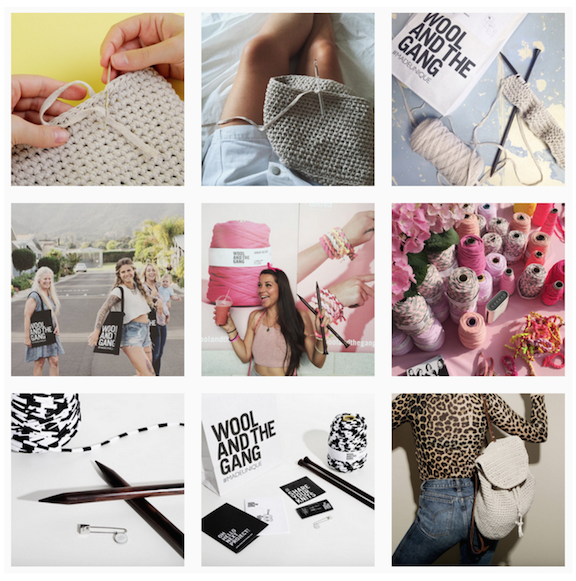

Even when crafts aren't monetized they often fall into the ecosystem of lifestyle branding. There are Pinterests devoted to quilting, Instagrams concentrated on embroidery. Ravelry is an entire social media platform for knitting and crocheting boasting nearly six million registered users. Karie Westermann, a professional knitter and knitting instructor, raised concerns on her blog about the “commodification of the ‘knitting lifestyle.’” She wrote, “The craft revival is precariously close to becoming Gooped,” referring to Gwyneth Paltrow’s lifestyle website. There’s an aspirational quality at play, both in the sense of presenting a perfectly desirable image (usually white, able-bodied, heterosexual, and middle class) and also with the goal of luring in sponsorship partners. “It feels like much of the ‘making’ out there,” she explained, “is now designed to get commercial brands interested in working with you rather than the crafting/making itself.”

But if someone succeeds in monetizing knitting through sponsored posts or goes pro with their hobby pickling vegetables, are they still going to take the same pleasure from it? And, ultimately is what defines a hobby the idea of escaping the pressures of work? Maines notes that over and over again in history, the same acts of labor become hedonized when we no longer have to do them. The latest example of this is cooking. “If you look at the economic census, kitchen renovations and cookbook sales are way up, but cooking is way down,” she says. As more and more people eat out and order in, she explains that “cooking is no longer a necessity, so when people do it, they’re weekend cooks or they’ll make blueberry jam or decorate a cake. It’s part of the hobby life.”

Maines thinks the reason might be, at least in part, psychological: “Typically if you have to do something, it becomes a chore even if it were something that was ordinarily enjoyable to do.” Trends in leisure activities certainly seem to reinforce the idea that work and pleasure are mutually exclusive categories, even if the same activities can be both labor and leisure.

But if it doesn’t feel like labor if you’re not getting paid, what about if someone else is? Web 2.0 companies like Facebook and Instagram profit off of the content we post for free during our leisure hours (or the downtime at white-collar bullshit jobs). “Play can be monetized as if it were work. All that free time people spend in games and on the internet,” notes Wark, “someone is always collecting the rent. Not to mention collecting all the data.” And so, surfing the web or posting pics (even if it’s of your latest crocheted cat sweater) is not just leisure but free labor, and perhaps ultimately just as alienating as the work that people try to escape with hobbies in the first place. ~*

-

Pursell, Carroll W. 2015. From playgrounds to PlayStation: the interaction of technology and play. ↩︎

-

Gelber, Steven M. 1999. Hobbies leisure and the culture of work in America. New York: Columbia University Press. ↩︎

-

Video—Middle Class Opportunity in American Cities During the Second Industrial Revolution. ↩︎

Whitney Mallett writes and makes videos. Her work has been published by The New York Times, ArtForum, Art in America, DIS, Vice, Arte TV, Topical Cream, and others.