In conversation with Tao Lin on his mandalas

Tao Lin interviewed by American Artist and Dorothy Howard

Dorothy Howard and American Artist: How long have you been making the Mandalas and about how many are there? Is it important that they form a series?

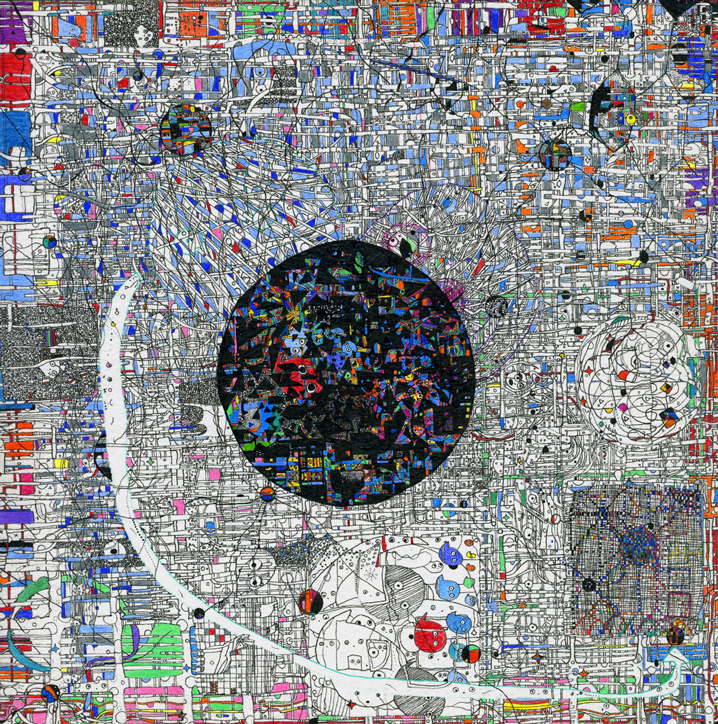

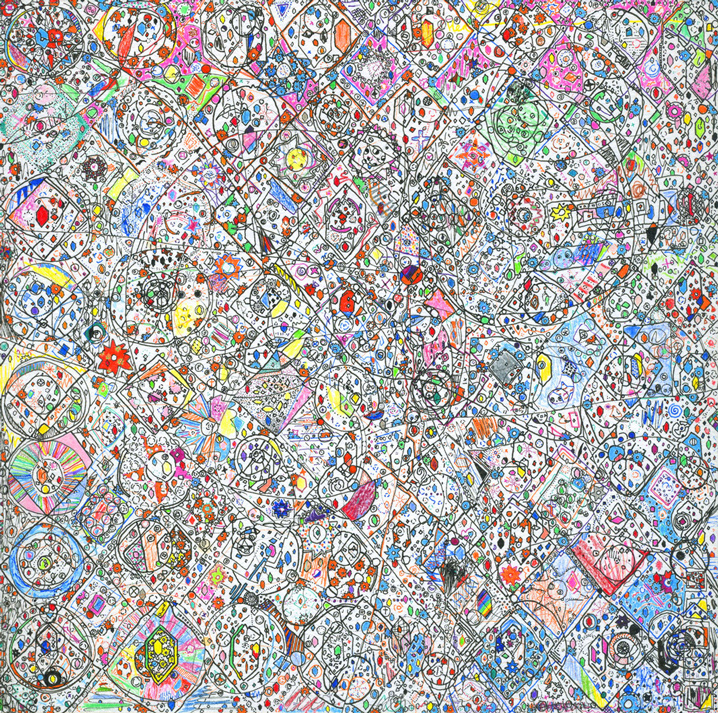

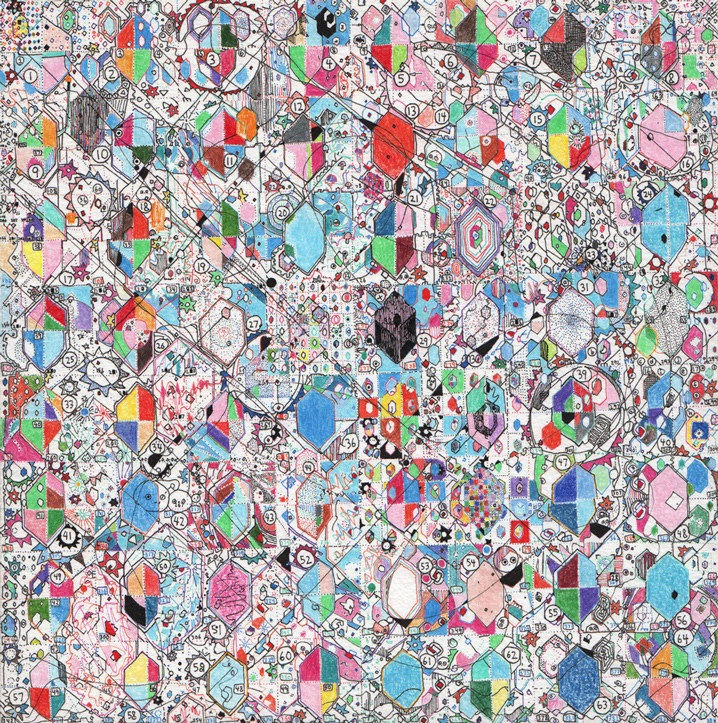

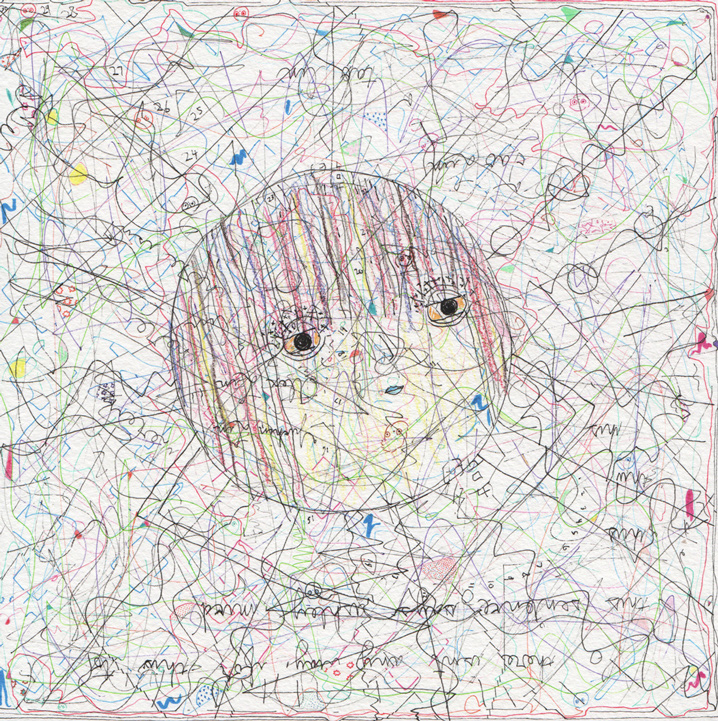

Tao Lin: I’ve been making them since February 2014. I’ve drawn 40–50 and abandoned around half. There are 12–14 that I view as finished and enjoy looking at and contemplating, most of which are here. There are also some like the neutral expression one that I spend less time on—like 1–5% of the time I spend on the other ones—and I want to call those mandalas also. I want to call anything I draw on 8" x 8" paper a mandala.

At first I wanted them to be in a chronological series. But now I think I want to put them into an only somewhat chronological series, putting them in order like I might stories in a story-collection or poems in a poetry-collection, after I finish a certain number of them in something like 2025 and am ready to publish them in a book.

Some of them are changed when viewed in a series. Many of them are divided into 64 parts in an 8x8 manner. In one of these I draw one of the 64 squares of the previous mandala as an entire mandala, zooming in like how people, looking at the visual component of their existence, can move toward a 64th portion of the image and see things that were not visible at a distance, like veins in leaves. I want to do this with 3 or 4 or 5 mandalas—draw 1/64th as an entire mandala, then 1/64th again and again.

DH / AA:The drawings reference mandalas, the spiritual devices found in religious aesthetics, but also seem to allude to more technological, network imagery. How did you decide to title the works Mandalas?

TL: On February 12, 2014 I was absently drawing on graph paper. I drew what looked to me like a crop-circle idea. I drew over it, adding layers. When I was finished it looked like a mandala, and the paper I was using was square, like in mandalas, so I called it a mandala. Three reasons I like calling these mandalas:

Tibetan Buddhist monks meticulously create complicated mandalas using colored sand, then dispose the sand in water, I saw in Werner Herzog’s documentary Wheel of Time. I don’t dispose my mandalas, but I’m reminded of the fleeting nature of things while drawing due to calling them mandalas.

Some mandalas, in the past, have represented the universe. Jung encouraged his patients to draw mandalas. He called them “psychological expression[s] of the totality of the self” which to me is also a representation of a world, the world of the self. I like to imagine all the mandalas I draw as representing a world, or many worlds overlapped. Some worlds I’ve imagined myself to be symbolizing while drawing: The world of my relationships with people. A world I might want to exist in—a place of more, rather than less, complexity and variety. A world I might like to explore. A world I will be forced to exist in at some point. A world someone I like will one day get to explore or be forced to exist in or be condemned to exclusively study for a thousand years.

I like to view this as a form I’m working in, like the novel form or short story form. The rules of this form are that I draw on 8" x 8" paper without a plan. I’m open to changing the rules because I want to try drawing a gigantic one at some point, like 4' by 4' maybe. I like to view this as a form because I’m interested in other people working in the same form and also drawing on 8" x 8" paper for hundreds of hours, especially people I’m friends with, because I think it would be fun to have multiple people making these.

DH / AA: Are the drawings made within the context of literature, or are they part of your writing process?–specifically perhaps in the way they circulate within social networks and blogs online through their dissemination as image files.

TL: Some connections these mandalas have with literature:

I’m almost always thinking about literature. I view existence as the first draft to possible literature. I view my internal monologue as literature. I view any word I think or say or hear as literature.

Some of these mandalas have characters and words and sentences written on them.

I will probably write about my experiences drawing these in fiction or an essay at some point, maybe in my next novel.

I’ve written almost daily since I started making these in February 2014 and I enjoy sometimes stopping writing to draw for 5 or 10 minutes, and while drawing I often get ideas in language that I then email myself or type into a file.

DH / AA: By releasing the work online, on your blog, through social media, and selling it through eBay you are making your drawings seemingly outside the market-driven art system. What is your intention in using these avenues of dissemination? Are you interested in critiquing the way art is monetized or made into a luxury good?

TL: I’m not critiquing anything, no. I haven’t thought much about what to do with these after making them. I enjoyed putting them on eBay because it outsources pricing. I haven’t been selling any since the first 10 or so that I sold on eBay because I like to look at them in a series, and to continue working on older ones that I’ve viewed as finished, and also because I anticipate making more money off writing than visual art, so I’m not thinking about making money off these.

DH / AA: Taipei was reblogged on a Subreddit about exploring activities through altered states of consciousness and has been discussed in terms of literature influenced by altered states of consciousness. Would you say that it’s a fair association to associate the Mandalas with art that explores the influence of altered states of consciousness on creative processes?

TL: Yes, that seems fair. I do explore the influence of altered states of consciousness while drawing these mandalas. I’ve been stoned on smoked and/or ingested cannabis probably 70–80% of the time working on these and maybe 40% of the time I’ve been under the effects of other substances like caffeine and various plant extracts.

But I don’t think the effects of these substances can be seen in the drawings. I don’t think different states of consciousness affect what I draw, at least for these mandalas. They more influence what I think and feel and remember and notice while I draw. While drawing, I enjoy modulating my consciousness via substances and monitoring my decision-making process and other aspects of my inner state.

I could draw one of these while only sober, or stoned, or on amounts of LSD where I can still draw, or on opiates or benzodiazepines or [anything where I can still draw on an 8" x 8" piece of paper for hundreds of hours], and people would not be able to discern differences in the mandalas I think. I could draw what I think people would associate with, say, LSD, but I feel that would be entirely me ceding to expectations and stereotypes of what LSD-art looks like, not a direct effect of the drug on my art.

DH / AA: In your personal blog you reference the conversation about art and relativity (re: conversations about ‘good and bad’ in art’s reception). What discussions about aesthetics are you interested in exploring in the production of the Mandalas?

TL: I’m interested in the following:

Encoding information. I sometimes view myself as drawing images that will be used to encode information. The more complex the image, the more information can be encoded. The more interconnected the image, the more information can be encoded. The more chaotic and unpredictable aspects that the image contains, the more information can be encoded. The more patterned the image, the easier that information can be encoded and decoded.

Remembering. I remember things I don’t normally remember when I draw these, especially while stoned. I remember childhood memories or other memories that surprise me, memories I’d forgotten. I remember dreams I’d forgotten—sometimes intensely, so I feel not like I’m remembering the dream but like I’m inside the dream again and it’s an explorable place not a fleeting occurrence in my mind in the past.

Ruining. With most of these mandalas, after working meticulously on it for ten or twenty or however many hours, creating a layer or layers of patterns, I start feeling bored of the image. I want to ruin it. I scribble wildly over it, or sometimes I scribble in a half-controlled manner over parts of it, and then it looks different and I enjoy working on it again. I enjoy drawing from that ruined state and gradually assimilating all the scribbles that oppose and/or ignore the previous patterns of the mandala by drawing more instead of erasing or editing as I would in writing. For some mandalas I do this multiple times—draw meticulously and consciously with at least some plan, ruin at least half-unconsciously and without a plan, carefully assimilate what I did without a plan.

DMT. For some of the time while working on some of the mandalas, I imagined myself trying to produce DMT imagery. Imagery that would remind me how it feels after smoking DMT. I wanted to do this not by drawing what one “sees” on DMT but by drawing something that might produce astonishment in the viewer, which is what—“astonishment”—DMT seems to produce in many people. Terence McKenna said that DMT reveals an unanticipated dimension—that it causes an experience that is impossible to imagine or suspect of existing until it’s happened. It’s around 2 corners, or beyond “beyond unexpected”. To model this aspect of DMT with visual art, I tried to draw unexpected, unanticipated images, or images that, when examined, might produce feelings of surprise in the viewer. A friend emailed me this after seeing one of the mandalas in person and I like it and want to try to do this more in the future: “ was more intricate than i feel like i was capable of imagining before seeing it irl”.

Drawing on four sides. Jackson Pollock wrote: “My painting does not come from the easel. I prefer to tack the unstretched canvas to the hard wall or the floor. I need the resistance of a hard surface. On the floor I am more at ease. I feel nearer, more part of the painting, since this way I can walk around it, work from the four sides and literally be in the painting.” With my mandalas, I don’t walk around the painting, but I turn the paper so that I “walk around” it. For many of the mandalas, I draw them from four sides, not knowing for sure until late in the process which side will be the “official” top side of the mandala—the side that will be on top when I look at it and show people in the future. Some of the mandalas can be viewed with each of the four sides as top. *~

Tao Lin is the author of the novels Eeeee Eee Eeee (2007), Richard Yates (2010), Taipei (2013) and other books. His most recent book is Selected Tweets (2015).

American Artist makes artwork around issues of authenticity and representation in the Information age. His work comes in the form of text, image, and conceptual intervention. This began with the change of his legal name to American Artist in 2013.

Dorothy Howard is a technology and media researcher, writer, and information activist. She focuses on digital labor, contemporary art, and online culture. Her first book of poetry, Troll was published by Inpatient Press (2015).