Hyper-invisibility and Blackness in Mexico: Encounters with the Self through encounters with history

Tiana Marie Mincey

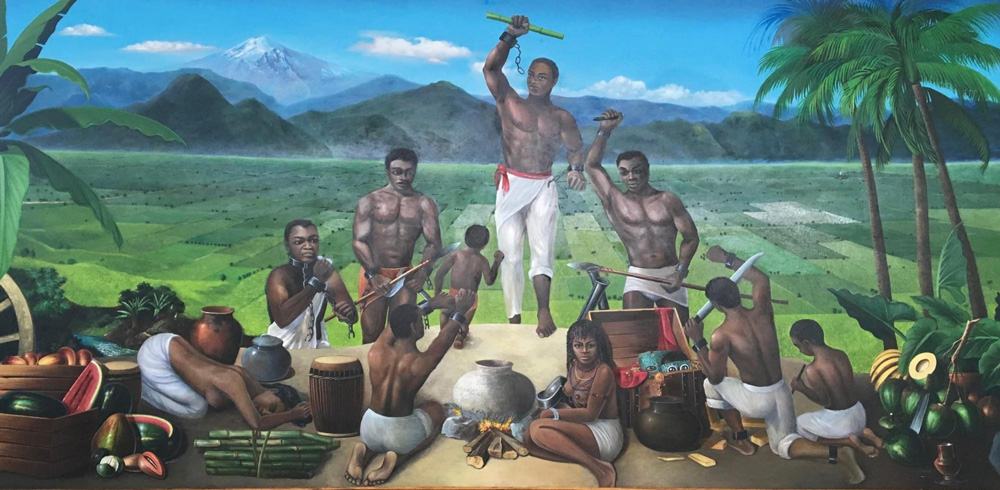

Painting at Museo Regional de Palmillas, Yanga Veracruz

People float around the globe today for a variety of reasons–from forced migration and seeking refuge, to a search for better opportunities, to leisurely vacations, to travel driven by a desire to better understand a particular problem or history. As globalization continues to take a toll on the world–manifesting in vast disparities of wealth inequality–it becomes more urgent to look at the way in which immigration, emigration, and the resulting diaspora of these processes within particular communities/countries affect status-quo conditions of an environment. The societal creation of borders, and nation-states, support often violent distinctions between those who can belong and seek residency within a space and those who can’t. These borders and agreed upon separations fuel an illusion of separateness, of there being an in group and an Other, and are also heavily backed by invented racial divisions. The proliferation of racial ideologies throughout history and the subjugation of different groups of people became convenient ways to delineate labor roles for centuries. Starting with four epistemicides (a war or destruction of a system of knowledge) of the 16th century (Grosfoguel, 2013) religious oppression and racial oppression have been strategically deployed to create and maintain class divisions, to distinguish realms of labor and to identify who is granted access to institutions and privilege which allow them to theorize and categorize the world.1 The continual effects of the invented concept of race are seen in the way race influences the nuances of cultural interactions up to present time. An examination of conversations and daily interactions, reveal the intricacies of the biases and and judgements that still exist today. Much can be understood in unpacking how strangers look at each other on the street, and how this is part of a larger cultural subjectification or gaze. I am interested in the way experiences, and physical movement around the planet (forced or voluntarily) reveal some of this history, or cause people on both sides of the encounter to examine local and structural biases, judgements, and class systems.

I frequently find myself in spaces where blackness is questioned, othered, stereotyped, stigmatized, targeted, blamed, or brought to the center of attention. I have become increasingly critical of the daily interactions that document these experiences, that provide the nuances of the ways these mindsets affect and view black bodies between the large-scale conversations about whether racial prejudice exists or matters or not.

It is from this perspective that I write to you of what I’ve observed about the reception of my physical presence in Puebla especially, and of a story of the African diaspora in Mexico.

I was in Mexico this past summer for a visual art residency in relation to fibers and material studies. I applied for the residency under the pretense of learning more about textile traditions in Mexico, and sharing my own practice of traditional quilt-making. The residency did not necessarily support me in any of the collected information within this text–yet, several seemingly simplistic conversations within the classroom environment about race led me to reflect on my daily hypervisibility and experience every time I left the classroom and entered the streets.

As I am a black woman who can speak Spanish, most people don’t usually guess that I am from the United States when I first meet them abroad. They often frequently assume Brazil, Cuba, and occasionally Nicaragua or Jamaica (due to my dreadlocks). Sometimes this experience of exotification extends to a pleasant hypervisibility but more often towards unwanted attention from the male-gaze, or shocked teenagers who gawk and point. Regardless, for people who have not been to the United States, I tend to break typical stereotypes of what people from there “should” look like, and this has led to many interesting responses throughout my movement through space around the globe, such as many conversations about where my family is “really” from.. “y sus padres, donde nacieron?” “y sus abuelos…" It is almost like in a way people really forget about the effects of the transatlantic slave trade, colonization and capitalism on our daily lives up to this very point. As if there aren’t millions of displaced people of color all over the Western Hemisphere. Somehow, though these polycultural historical roots are not often considered in the images of the types of people that could arrive from a specific country.

The attention my physical features attract follows me everywhere in Puebla. I naively thought I would feel really comfortable all over Mexico but surprisingly the stares and smirks and points are an every intersection occurrence here. From people tripping while walking down the street, to cars stopping traffic, to folks grabbing me and wanting to photograph me as I try to get from class to my space of residency, I am constantly reminded that my presence is not common. I realized today though that despite wanting to wear a shirt saying “si, soy un serhumano”… while some have weird preconceptions about where I should exist in the world, others at the same time have fantasies about having little “morenita” babies. When my skin-tone becomes a fetish in this context, I feel that this exotification may actually be coming out of a (relatively?) less mal-intended place of finding beauty in difference. So at least my hyper-visibility frequently comes with less negative connotations here then it may even in some places in the U.S.

My experiences in Puebla are about more than being an African-American woman who can speak Spanish; they are about the stigmas that exist globally regarding skin tonality, specifically darker skin tones. They depict the obsessive pigmentocracy that exists in different nuanced ways in interactions in the United States and in Mexico. In academic discourse in Mexico, class is emphasized as the main determinant of societal status, the amount of money, posture, education, the general way a body interacts with space. There are also fewer people of African heritage here for racism to be highlighted in the same binary ways it is often redacted to in the United States. Today’s Afro-Mexicano population can be found primarily in the coastal regions of Oaxaca, Veracruz, and Acapulco and have only in the last year gained recognition as a group in the Mexican National Census. The 2015, National Mexican Census found that there were about 1.38 million people of African descent (about 1.2% of the country’s population).2

Outside of the Afro-Mexican communities, and those with occasional fantasizing of having hijos morenitos–I have still discovered in conversations with many locals an appreciation and preference of lighter skin tones, for many there is a genuine fear of becoming too dark or too negro. In a conversation with a young woman my age, she recounted to me the pressures for her family to keep her darkest child out of the sun, to have him in long-sleeves and pants in the hot mexican summers so that he wouldn’t become more and more negrito. She recounted that at age 5 he already compares himself to his much lighter-skinned younger sister and asks why he didn’t come out like her.

In the attempt to process these experiences in Puebla and connect how race is viewed and taught through subconscious behaviors, I am recalled by another experience I had there in a Hiper-Lumen artist supply store outside of El Carmen Parque on the streets of 17 Poiniente y 16 de Septiembre. As I walked around looking at pencils and notebooks and translating the prices from pesos to dollars in my head, I encountered a dad with three daughters none of which could have been older than 9. I smiled at the girls, and waved and they smiled back and waved instantly and normally and continued ranting to their father about which items they were most interested in. It was really quite innocent and normal but their dad had looked up and not been able to stop staring at me with a peculiar expression like I didn’t belong. As I moved into the next few aisles they were quickly moving along at relatively the same speed, and their father continued to not be able to take his eyes of me. Of course the chattering girls eventually noticed the way their father kept staring at me out of the corner of his eye and you could see the realization click into their brains looking at him and then me–that wait actually I was pretty different looking, out of place and there was a lot more to stare at with my dark skin and dreadlocks then they had initially realized. Experiences such as these continue to exhibit how behaviors are learned, how the invented concept of race continues to be passed down through behaviors and conversations from parents to children as well as through more systematic social systems.

These questions and personal experiences opened up a desire to know more about the Afro-descendant communities here in Mexico as a way of locating the things that I saw within historical threads. These threads brought me closer to the Atlantic coast, to Veracruz.

Still here: A deeper look at history

The first place slaves were freed in all of the Americas was in Veracruz, Mexico in 1609. Eleven years before the Mayflower even landed in what is today the United States of America, the first self-freed slave communities (Cimarrones) were formed here, in Veracruz, Mexico, by Gaspar Yanga an enslaved and then self-liberated African believed to be from Ghana, Angola, or Gabon depending on which source you consult. His community was called San Lorenzo de Los Negros at the time and still exists today, though by now the descendants have re-named it Yanga in his honor.

I went to Yanga to learn more about this history. Upon arrival I befriended an older man who told me that he lived in one of the Cimarron communities, El Mirador. Through cane field after cane field in the back of an open truck we rode, occasionally picking up people, tamales de elote, and a big jug of fresh, pure pineapple juice.

In a day when even back at home my grandparents would call days in advance before coming over from their house a few blocks away, I was shocked at how welcoming the people in this small town were when we arrived spontaneously. They opened up their doors easily, telling me who to contact, and sharing stories about people who had visited before searching for answers about the history of Yanga.

Through a chain of people I received pieces of the story, of Yanga, the mystery of his birth, and the mystery of his death. He fought for the land around the Pico de Orizaba for 39 years from 1570, until Spain acknowledged San Lorenzo de Los Negros as a self-governing municipality.3 This area surrounding Cordoba became an important place for the Spanish to conquer because of its prime location in the center of the route between Veracruz and Mexico City. Today the traditions and spirit of Yanga are still kept alive by hosting a Carnaval held every August, where a king and a queen are selected in three age groups to organize traditional events throughout the year to honor historical customs of dance, dress, and celebration.

The people in this area of Yanga, from El mirador, to Mataclara consider themselves “Afro-descendientes” (African-descendants). Most are proud of their roots but also aware of their invisibility within the larger image of Mexico. Over dinner one evening with a lovely welcoming family in Mataclara we passed around bowls of arroz rojo, frijoles, spicy pollo frito, and fresh tortillas as we discussed race relations and experiences of invisibility here in Mexico. The family invited a guest over for dinner, an internationally well-known Jarocho player (a Veracruzano style of music) who came over just to play for me and to share his music and story. This magnificent dark-skinned Jarocho player recounted his experiences with people not believing that he was from Mexico as he traveled around the country. With skin as dark as mine, and similar features, many of the dinner guests had similar experiences of being read as “gringos” at times even here in their own home-country. Few people outside of Veracruz have heard about Yanga.

So in a country where there was once an estimated 200,000 people of color enslaved and brought over from Africa. One might ask how did it come to be that dark skin became such a rarity? Mestizaje or the hybridity of native and Spanish roots has been emphasized as the roots of lineage for the majority of Mexico’s citizens. Many descendants of Africans became very mixed with indigenous races throughout all of Mexico, and almost everyone has some percentage of African ancestry in their lineage, as the new national consensus indicates. There are plenty of darker people in Mexico who still would identify as mixes of indigenous races, negating any connection with Black, or African ancestry, as the absence of this option on the national census also proliferated. There are still whole communities surviving, in the outskirt sierra regions of Veracruz, and Oaxaca’s Costa Chica that remain undiscussed, just being acknowledged for the first time on Mexico’s national census in the last year.

Much of the history of Yanga remains hidden, and there are one or two dedicated historians from the area working to do so and writing about it, such as Puebla native Antonio Carrerra. Many of the people of Yanga want their history to be known, want their town to have more tourism options other then still mainly surviving off of sugar-cane work. Many of my conversations with folks born and raised in this area have revealed a desire for a better system of organization so when visitors come from overseas they can learn, and engage and contribute rather than just gawk for a few moments at Afro-descendientes and head out. It is perhaps time for new ethical advancements in labor and technology here in Yanga to a degree, to fuel a community that desires to be recognized, known about and have its pride documented. These potential advances within the system of Yanga can help to share the stories and traditions and bring the presence of Afro-Mexicano’s out from the rural sugar-cane fields to a recognized part of Mexico’s population. These experiences remind me of the need to remove these social stigmas associated with African-descendancy, to remove the creation of differences through pigmentocracy and standards of beauty that continue to affect people with darker skin tones to this day. These beliefs, prejudices and subconscious behaviors are passed down from parents to children in the most subliminal ways. It is time to move past historically rooted systems of “purity of blood” and of the societal benefits of being visually closer to whiteness that were what the foundation of Mexico was built on since implemented as strategies of colonization during the Spanish inquisition. The history in this region is a testament that, cane field, after cane field for miles and miles, in little dirt road towns with small houses and large families, the Afro-Mexicano community still survives.

A sculpture in the park in the center of Yanga, Veracruz

Self-portrait in the sugar cane fields surrounding Yanga, after walking for miles through the outskirts

-

Human Architecture: Journal of the Sociology of Self-knowledge, XI, Issue 1, Fall 2013 ↩︎

-

Sameer Rao, “Mexico Finally Recognizes Afro Mexicans in National Census.” COLORLINES, December 14, 2015 http://www.colorlines.com/articles/mexico-finally-recognizes-afro-mexicans-national-census ↩︎

-

Bennett, Herman L. Africans in Colonial Mexico: Absolutism, Christianity, and Afro-Creole Consciousness, 1570–1640. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 2003. Print. ↩︎

Tiana Marie Mincey is an interdisciplinary artist and creative from Montclair, NJ. She is passionate about cooking, living and eating well and combining her artistic practice with her interest in histories and broader fight for human rights. A traveler, a writer, a dreamer, and a visual artist, her work is about bridging connections across differences, and re-centering globally and historically under appreciated systems of knowledge.